Practice techniques

Golf's lesons for Musicians by Scott Moore

30/07/19

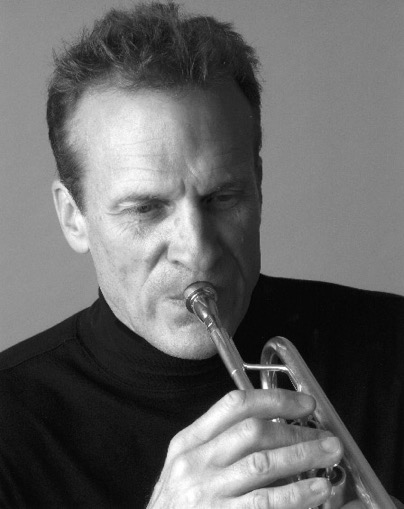

Scott Moore and I were at New England Conservatory together. He is principal trumpet in the Memphis Symphony Orchestra and is an avid golfer. He has a clear perspective on the skill set needed to master golf and trumpet.

WHAT GOLF TAUGHT ME ABOUT BEING A MUSICIAN

After five days straight of watching the greatest golfers in the world at the WGC FedEx-St Jude Invitational Golf Tournament, I have learned a lot, and have been newly inspired.

But not like you'd think.

Most people ask if watching them helps me with my golf game. I suppose that it's good to be reminded that pros miss short putts too, but the game they play is so different from the one I play that I would be delusional to try to emulate those guys on the golf course.

Where I CAN emulate them is in what I do best: playing the trumpet. Most upper-level professional golfers have routines and performance characteristics that transfer very well to trumpet playing and music performance in general.

DAILY EMPHASIS ON FUNDAMENTALS: Every pro on the driving range begins by working on alignment, grip, posture, stance, swing plane, etc., assisted by alignment aids and the best technology available. It's a fantastic reminder that fundamentals are not something to be learned and then checked off of a to-do list—they are a daily endeavor. And that we should monitor our routine and progress with some of the myriad of technological tools available to musicians.

PRACTICE WITH A PURPOSE: Pros work through their entire golf bag, hitting several different types of shots with each club, so they are prepared for every type of shot they will have to hit on the golf course. They do not avoid the things they are uncomfortable with, but rather work to turn their weaknesses into strengths.

HIT THE SWEET SPOT: There is an unmistakable difference in the sound of a professional hitting a golf ball. When the sweet spot of a club makes contact with the golf ball, the ball goes farther and straighter with less effort. Likewise, in all musical instruments, there is a sweet spot, where the instrument naturally is more resonant and lively. When we consistently hit that spot, we achieve a more beautiful, resonant, projecting tone with less effort.

VISUALIZE SUCCESS: Before every shot, pros stand behind the ball and "see" the shot they are about to make in their mind. They envision the flight of the ball and its landing area. They are skilled at thinking about what can go right, and eliminating thoughts about what can go wrong. How can we play something beautifully if we do not first hear it that way in our heads?

PLAY SMART: Pros always have a plan. They know where to aim their shot, in order to have a good angle on their next shot. They never take unnecessary risks. They are always thinking ahead, never behind.

ATTENTION TO DETAIL: Pros factor in every conceivable variable before hitting a shot: the exact distance, the wind, the temperature, the grain of the grass, the lie from which they will make their shot, etc. Musicians have so much information available to us in the way of dynamics, articulation, note length, etc. Too often, those details are not given the full attention that the music deserves.

DO NOT LET MISTAKES DERAIL YOU: Every single pro makes mistakes. But the worst outbursts of temper I saw were nothing compared to those I see from amateurs on public golf courses on a regular basis (yours truly included). For the pros, a missed putt can cost them tens of thousands of dollars. So what do I have to get angry about? Pros will be momentarily irritated, then immediately begin thinking of their next shot. Their ability to remain focused despite having made a huge mistake, or getting a bad break, is awe-inspiring. How many musical performances have gone downhill quickly when a musician gets angry at a mistake, and then mistakes begin coming in faster and faster? This ability to remain unflappable is also related to:

DO NOT LET YOUR SUCCESSES DESTROY YOUR FOCUS: Even after making an amazing shot or draining a long birdie putt, pros will respond to the crowd with a brief hat tip or wave of the hand. They are already thinking about the next hole, and the shot they will hit from the tee box. As trumpet players say, "The hardest note is the one after the high note." Loss of focus is deadly.

GOLF IS HARD: no need to explain the similarity here.

WHAT GOLF TAUGHT ME ABOUT BEING A MUSICIAN

After five days straight of watching the greatest golfers in the world at the WGC FedEx-St Jude Invitational Golf Tournament, I have learned a lot, and have been newly inspired.

But not like you'd think.

Most people ask if watching them helps me with my golf game. I suppose that it's good to be reminded that pros miss short putts too, but the game they play is so different from the one I play that I would be delusional to try to emulate those guys on the golf course.

Where I CAN emulate them is in what I do best: playing the trumpet. Most upper-level professional golfers have routines and performance characteristics that transfer very well to trumpet playing and music performance in general.

DAILY EMPHASIS ON FUNDAMENTALS: Every pro on the driving range begins by working on alignment, grip, posture, stance, swing plane, etc., assisted by alignment aids and the best technology available. It's a fantastic reminder that fundamentals are not something to be learned and then checked off of a to-do list—they are a daily endeavor. And that we should monitor our routine and progress with some of the myriad of technological tools available to musicians.

PRACTICE WITH A PURPOSE: Pros work through their entire golf bag, hitting several different types of shots with each club, so they are prepared for every type of shot they will have to hit on the golf course. They do not avoid the things they are uncomfortable with, but rather work to turn their weaknesses into strengths.

HIT THE SWEET SPOT: There is an unmistakable difference in the sound of a professional hitting a golf ball. When the sweet spot of a club makes contact with the golf ball, the ball goes farther and straighter with less effort. Likewise, in all musical instruments, there is a sweet spot, where the instrument naturally is more resonant and lively. When we consistently hit that spot, we achieve a more beautiful, resonant, projecting tone with less effort.

VISUALIZE SUCCESS: Before every shot, pros stand behind the ball and "see" the shot they are about to make in their mind. They envision the flight of the ball and its landing area. They are skilled at thinking about what can go right, and eliminating thoughts about what can go wrong. How can we play something beautifully if we do not first hear it that way in our heads?

PLAY SMART: Pros always have a plan. They know where to aim their shot, in order to have a good angle on their next shot. They never take unnecessary risks. They are always thinking ahead, never behind.

ATTENTION TO DETAIL: Pros factor in every conceivable variable before hitting a shot: the exact distance, the wind, the temperature, the grain of the grass, the lie from which they will make their shot, etc. Musicians have so much information available to us in the way of dynamics, articulation, note length, etc. Too often, those details are not given the full attention that the music deserves.

DO NOT LET MISTAKES DERAIL YOU: Every single pro makes mistakes. But the worst outbursts of temper I saw were nothing compared to those I see from amateurs on public golf courses on a regular basis (yours truly included). For the pros, a missed putt can cost them tens of thousands of dollars. So what do I have to get angry about? Pros will be momentarily irritated, then immediately begin thinking of their next shot. Their ability to remain focused despite having made a huge mistake, or getting a bad break, is awe-inspiring. How many musical performances have gone downhill quickly when a musician gets angry at a mistake, and then mistakes begin coming in faster and faster? This ability to remain unflappable is also related to:

DO NOT LET YOUR SUCCESSES DESTROY YOUR FOCUS: Even after making an amazing shot or draining a long birdie putt, pros will respond to the crowd with a brief hat tip or wave of the hand. They are already thinking about the next hole, and the shot they will hit from the tee box. As trumpet players say, "The hardest note is the one after the high note." Loss of focus is deadly.

GOLF IS HARD: no need to explain the similarity here.

Chris Gekker's Summer Practice Routine

07/07/19

When the dog days of summer hit, Chris Gekker's routine will keep your chops in shape when it is easy to let it all slide.

Summer is a good time to reconnect with our most basic practice. Practicing the basics can be interpreted many different ways – here is one approach that works well. You will need four books:

•. Herbert L. Clarke: Technical Studies

•. Schlossberg: Daily Drills

•. Arban: Grand Method

•. Sachse: 100 Etudes

Start with the Clarke

These can be done effectively many different ways, but this time let’s do them just as Clarke intended: start each study in the lowest possible key, very very soft. The idea is to become adept at an extremely relaxed, economical way of playing. We must have a very secure, efficient sense of air support, and a pliant, flexible aperture supported by a strong, stable embouchure. Though we will sometimes ascend to some of our highest notes, in general our playing should be very “conversational” – a good image to keep is of a very well tuned car engine, that can idle so quietly that the driver is not aware that the car is running. For the most part you will be playing softer than you would normally do in performance, so do not be too concerned with your tone quality – you are “tuning your engine,” connecting with your instrument on an extremely relaxed level.

Do one study a day. This makes a very nice eight-day cycle, where we hit our fundamentals every day within the framework of varying demands.

No. 1 – At least eight times in one breath. Whisper soft. Once you are in the middle register, legato tongue a few of them (four times through when tonguing).

No. 2 – Each one twice, at first. Stop where Clarke stops, don’t continue into the high register (this is meant to be an “easy” day). After you are very comfortable with these drills, go through each one four times: slurred, single tongue, K tongue, and double tongue – and keep the tempo the same throughout.

No. 3 – Each one twice. Work in some tonguing after you learn the patterns. Keep striving to be able to play these softly.

No. 4 – Play using the same approach as No. 3.

No. 5 – On this one we can open up dynamically as we ascend to the highest notes. Keep as much of it as “conversational” as possible. For now, skip the scale exercises 99-116.

No. 6 – Play these just as written, so the tongued arpeggios at the end are in contrast to the slurred material.

No. 7 – Again, work in some tonguing as you get comfortable technically. Stay as soft as possible. For now, skip the arpeggio exercises 151-169.

No. 8 – Play using the same approach as No. 7.

On your first few cycles, omit the etudes at the end of each study. After the studies are fairly well learned, start to learn them. I usually tongue the etude after going through the studies where I use a mixture of slurring and legato tonguing. Clarke recommends a fair amount of multiple tonguing practice – I prefer to stick to legato single tonguing, except for the drill on the Second Study.

Next come the Schlossberg Daily Drills

I like to set up a shorter cycle for these – here is a good three-day routine. With Schlossberg, we’ll use our metronomes and will try to keep in mind James Stamp’s advice, to “think down when going up, and up when going down.” Really listen to your sound on these, but remember what Arnold Jacobs has taught: do not be obsessed with how you sound; rather, play to an ideal tonal concept that hopefully you are continually cultivating internally.

Day 1

No. 9 Quarter = 40 Rest at the end of each line. Play mezzo forte throughout

No. 17 Half = 60 Full sound, very well projected. Marcato, but no short notes

No. 25 Quarter = 120 Fast and light, very soft, single tongue throughout

No. 32 Quarter = 120 Tongue the downbeat of each measure. Dolce, but full sound

No. 72 Quarter = 80 mp to mf, single tongue throughout, nice and crisp

No. 116 Quarter = 96 Done as one, crisp and clear

No. 117 Quarter = 96 Crisp and clear.

Day 2

No. 10 Quarter = 40 Follow Schlossberg’s dynamics. Rest a bit at the double bars.

No. 18 Quarter = 80 Legato tongue every note, very soft.

No. 30 Quarter = 60 Very full, well projected, as exciting as possible.

No. 63 Eighth = 120 Mf, alternate between slurred and legato tongue

No. 76 Quarter = 60 Very strong, marcato.

No. 93 Quarter = 80 Rest between each one, very full and strong.

No. 118 Quarter = 96 Crisp and clear.

Day 3

No. 13 Quarter = 40 Think “up” as you go “down” – do not telegraph your slurs.

No. 20 Half = 60 Legato tongue, singing sound.

No. 64 Quarter = 60 mf, alternate between slurred and legato tongue

No. 78 Eighth = 96 Very strong, marcato.

No. 82 Quarter = 80 Rest between each one, very full and strong

No. 99 Quarter = 80 Crisp and well projected.

No. 100 Quarter = 80 Same as No. 99.

No. 119 Quarter = 96 Same dynamic throughout, somewhere between p and mf, all in one breath.

Now it’s time for etudes

After you’ve rested a while, turn to the 14 Characteristic Etudes in the Arban Grand Method. Aim for one a day – it takes two weeks to get through them. For the first two cycles through I like to use a practice routine adapted from Claude Gordon. It will take 20-30 minutes to go through each etude, but they will mostly be learned in one day. Don’t use the metronome a lot on these, just occasionally after they’ve been learned, to experience at least some of each etude at Arban’s tempos. The language of this music requires a kind of flexibility that rules out using a metronome throughout.

Here is the version of Claude Gordon’s method. We’ll start with No. 1. Play the last four measures four times. Move four measures further toward the beginning, and do those four times. Then play the last eight measures to the end. Go to twelve measures before the end, and do those four measures four times, followed by the last twelve measures to the end. Keep working to the beginning of the etude, doing four reps of each four bar segment, followed by a run to the end of the etude from the section you did your reps with. Take enough rest throughout so that you stay relatively fresh. As your run-throughs get longer and longer, insert some short rests if you feel yourself getting tight. This routine will toughen your mind, and once you get the hang of it you will never again need a week to learn an etude.

Note that the Clarke Studies cycle every eight days, the Schlossberg every three days, and Arban every 14 days. So while you are relearning and reaffirming your fundamentals every day, each day is also different.

If you are involved with a heavy performing schedule, do not try to practice hard. You can only improve your playing when you have time to recover properly. I believe that the Clarke studies are very beneficial even when doing a high volume of rehearsals and concerts, but you may want to save the Schlossberg and Arban for lighter days. Only experience will teach you, and we are all different in some ways from each other. But this principle is true for all of us: improving and getting stronger requires that we all work very hard, and rest adequately. One without the other does not work.

Assuming that you can practice fairly consistently, after one month you will have gone through the Clarke studies 3 or 4 times, the Schlossberg drills 9 or 10 times, and the Arban etudes twice or so. At this point I like to make a few changes.

Keep your Clarke routine the same. It may be hard to imagine, but many prominent trumpeters have made a point of doing the Clarke studies for years. Keep in mind the old adage “form follows function” – if, on a daily basis, you establish a very efficient, relaxed approach to playing the trumpet, you will eventually become a trumpeter that can, on a daily basis, play the trumpet in a relaxed, smooth, and expressive manner.

We’ll now change our routine a bit.

After Clarke, alternate days of Arban and Sachse 100 Etudes. On your Arban day, keep working on the 14 Characteristic Etudes, one a day. Try this: do the last third or so a couple of times, the middle third twice, and the same with the first third. Rest at least five minutes, and try to play all the way through. With Sachse, start with No. 1, and do it in every transposition you can, including ones that might not be indicated. After this month of practice, you should be through about 15 of them. I recommend setting a goal of eventually doing all 100, in every key possible, which will take about two years. (As a student, I needed more than three, because I found it very hard to keep working on these when I was sounding so bad. After I was about halfway through the etudes, I started seeing real results, and was much more motivated to continue.) Transposition needs to eventually be as automatic as possible and the trumpeter that relies on formulas will be easily rattled under pressure. Formulas are necessary to help us learn how to transpose, but if you are serious you will want to progress to the point where you do not have to rely on them. The only way to make transposition nearly automatic is through learning a large volume of material over a fairly long time, which the Sachse book is made for. Many other benefits will be evident, if you persist on these etudes in every key possible. Mix up your approach – one day, start at the lowest key and work up by half steps. Another day, do the reverse. You can also start in the middle, and progress in half steps, alternating going up and going down, so you radiate outward from the middle.

After your etude work, rest awhile. At this point we’ll alternate our Schlossberg work with a book like Charles Colin Lip Flexibilities. You should by now have a good command of the Schlossberg exercises, and can start to perform them with more intensity (wider dynamic contrasts, more variety in styles of articulation). When these exercises a played really well, they can sound like very dramatic orchestral excerpts. On alternate days, do this routine from the Charles Colin book – No. 3, No. 9, No. 21, and pages 35 & 36. If your high D is coming out with ease, move on to the next level, but stick to about five exercises. Remember that these are primarily tongue level exercises, and must be performed with a dynamic, powerful air stream in order to realize the benefits. Rest at least as long as you play.

The reason we have switched the order is to make our practice routine a bit more in line with what sport medicine research has taught us about how to improve and get stronger. Begin by connecting with your body on a relaxed easy level, then move on to skill practice, and end by working on our power and strength.

Here are a few other ideas for summer practice

1) Pick one or two of our most challenging excerpts, and really work toward mastering them. Two that most trumpeters will have to contend with many times are the Ballerina’s Dance from Petroushka and the Ravel Piano Concerto. Since they present some of the same problems, this approach will work well for both. Do 20 reps of either excerpt at a session, like this – 5 times at Quarter = 96. 5 times at Quarter = 108. 5 times at Quarter = 126 (this will not really be possible for most players, but hang in there and do your best). And then 5 times at Quarter = 108-116 (this is a common performance tempo and will feel relatively easy after what you have just gone through!). If you devote a month or two to each excerpt this way, you develop the skill and reflexive memory that will allow you to quickly reclaim these solos whenever you have to play them in the future.

2) Find a recording of an improvised solo that you really like, and memorize it – not just temporarily, but so you can play it for anybody, anytime. If your approach is based on bebop, try learning a couple of Louis Armstrong’s solos, like West End Blues or Weather Bird. Or go the other direction, something more modern, like Woody Shaw, Booker Little, or Lester Bowie. Try something from another instrument, some Lester Young, or maybe Sonny Rollins. But find something you can really learn and play – many of the great innovators, such as Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, could play many solos by their favorite players, such as Lester Young or Roy Eldridge, by memory.

2) Find a recording of an improvised solo that you really like, and memorize it – not just temporarily, but so you can play it for anybody, anytime. If your approach is based on bebop, try learning a couple of Louis Armstrong’s solos, like West End Blues or Weather Bird. Or go the other direction, something more modern, like Woody Shaw, Booker Little, or Lester Bowie. Try something from another instrument, some Lester Young, or maybe Sonny Rollins. But find something you can really learn and play – many of the great innovators, such as Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, could play many solos by their favorite players, such as Lester Young or Roy Eldridge, by memory.

Memorization is not a special virtue in itself, but being able to play music by memory, whether a transcription of a great improvisation or a favorite etude, allows us to practice in a very productive way. When we can play without constantly looking at a page of written music, we often hear ourselves better and can really connect with our playing, both consciously and subconsciously. The method described earlier of learning the Arban etudes (working from the back to the front) is a very effective way to memorize music. When you get in the habit of doing some of your practice in this way, you will find that you will temporarily memorize whatever music you are working on.

3) If you are planning a recital in the coming year, begin working on deciding the repertoire and get some real time in on playing through it, making a special point to isolate and master the hardest parts.

Finally, if you are lucky enough to find yourself around some really fine musicians, play for them – especially if they are not trumpeters. Ask them to criticize you as hard as they can. Write down what they say, so you can think about it. What they say might not make a lot of sense at first, but you may find yourself eventually learning things that will surprise you.

Chris Gekker

Summer is a good time to reconnect with our most basic practice. Practicing the basics can be interpreted many different ways – here is one approach that works well. You will need four books:

•. Herbert L. Clarke: Technical Studies

•. Schlossberg: Daily Drills

•. Arban: Grand Method

•. Sachse: 100 Etudes

Start with the Clarke

These can be done effectively many different ways, but this time let’s do them just as Clarke intended: start each study in the lowest possible key, very very soft. The idea is to become adept at an extremely relaxed, economical way of playing. We must have a very secure, efficient sense of air support, and a pliant, flexible aperture supported by a strong, stable embouchure. Though we will sometimes ascend to some of our highest notes, in general our playing should be very “conversational” – a good image to keep is of a very well tuned car engine, that can idle so quietly that the driver is not aware that the car is running. For the most part you will be playing softer than you would normally do in performance, so do not be too concerned with your tone quality – you are “tuning your engine,” connecting with your instrument on an extremely relaxed level.

Do one study a day. This makes a very nice eight-day cycle, where we hit our fundamentals every day within the framework of varying demands.

No. 1 – At least eight times in one breath. Whisper soft. Once you are in the middle register, legato tongue a few of them (four times through when tonguing).

No. 2 – Each one twice, at first. Stop where Clarke stops, don’t continue into the high register (this is meant to be an “easy” day). After you are very comfortable with these drills, go through each one four times: slurred, single tongue, K tongue, and double tongue – and keep the tempo the same throughout.

No. 3 – Each one twice. Work in some tonguing after you learn the patterns. Keep striving to be able to play these softly.

No. 4 – Play using the same approach as No. 3.

No. 5 – On this one we can open up dynamically as we ascend to the highest notes. Keep as much of it as “conversational” as possible. For now, skip the scale exercises 99-116.

No. 6 – Play these just as written, so the tongued arpeggios at the end are in contrast to the slurred material.

No. 7 – Again, work in some tonguing as you get comfortable technically. Stay as soft as possible. For now, skip the arpeggio exercises 151-169.

No. 8 – Play using the same approach as No. 7.

On your first few cycles, omit the etudes at the end of each study. After the studies are fairly well learned, start to learn them. I usually tongue the etude after going through the studies where I use a mixture of slurring and legato tonguing. Clarke recommends a fair amount of multiple tonguing practice – I prefer to stick to legato single tonguing, except for the drill on the Second Study.

Next come the Schlossberg Daily Drills

I like to set up a shorter cycle for these – here is a good three-day routine. With Schlossberg, we’ll use our metronomes and will try to keep in mind James Stamp’s advice, to “think down when going up, and up when going down.” Really listen to your sound on these, but remember what Arnold Jacobs has taught: do not be obsessed with how you sound; rather, play to an ideal tonal concept that hopefully you are continually cultivating internally.

Day 1

No. 9 Quarter = 40 Rest at the end of each line. Play mezzo forte throughout

No. 17 Half = 60 Full sound, very well projected. Marcato, but no short notes

No. 25 Quarter = 120 Fast and light, very soft, single tongue throughout

No. 32 Quarter = 120 Tongue the downbeat of each measure. Dolce, but full sound

No. 72 Quarter = 80 mp to mf, single tongue throughout, nice and crisp

No. 116 Quarter = 96 Done as one, crisp and clear

No. 117 Quarter = 96 Crisp and clear.

Day 2

No. 10 Quarter = 40 Follow Schlossberg’s dynamics. Rest a bit at the double bars.

No. 18 Quarter = 80 Legato tongue every note, very soft.

No. 30 Quarter = 60 Very full, well projected, as exciting as possible.

No. 63 Eighth = 120 Mf, alternate between slurred and legato tongue

No. 76 Quarter = 60 Very strong, marcato.

No. 93 Quarter = 80 Rest between each one, very full and strong.

No. 118 Quarter = 96 Crisp and clear.

Day 3

No. 13 Quarter = 40 Think “up” as you go “down” – do not telegraph your slurs.

No. 20 Half = 60 Legato tongue, singing sound.

No. 64 Quarter = 60 mf, alternate between slurred and legato tongue

No. 78 Eighth = 96 Very strong, marcato.

No. 82 Quarter = 80 Rest between each one, very full and strong

No. 99 Quarter = 80 Crisp and well projected.

No. 100 Quarter = 80 Same as No. 99.

No. 119 Quarter = 96 Same dynamic throughout, somewhere between p and mf, all in one breath.

Now it’s time for etudes

After you’ve rested a while, turn to the 14 Characteristic Etudes in the Arban Grand Method. Aim for one a day – it takes two weeks to get through them. For the first two cycles through I like to use a practice routine adapted from Claude Gordon. It will take 20-30 minutes to go through each etude, but they will mostly be learned in one day. Don’t use the metronome a lot on these, just occasionally after they’ve been learned, to experience at least some of each etude at Arban’s tempos. The language of this music requires a kind of flexibility that rules out using a metronome throughout.

Here is the version of Claude Gordon’s method. We’ll start with No. 1. Play the last four measures four times. Move four measures further toward the beginning, and do those four times. Then play the last eight measures to the end. Go to twelve measures before the end, and do those four measures four times, followed by the last twelve measures to the end. Keep working to the beginning of the etude, doing four reps of each four bar segment, followed by a run to the end of the etude from the section you did your reps with. Take enough rest throughout so that you stay relatively fresh. As your run-throughs get longer and longer, insert some short rests if you feel yourself getting tight. This routine will toughen your mind, and once you get the hang of it you will never again need a week to learn an etude.

Note that the Clarke Studies cycle every eight days, the Schlossberg every three days, and Arban every 14 days. So while you are relearning and reaffirming your fundamentals every day, each day is also different.

If you are involved with a heavy performing schedule, do not try to practice hard. You can only improve your playing when you have time to recover properly. I believe that the Clarke studies are very beneficial even when doing a high volume of rehearsals and concerts, but you may want to save the Schlossberg and Arban for lighter days. Only experience will teach you, and we are all different in some ways from each other. But this principle is true for all of us: improving and getting stronger requires that we all work very hard, and rest adequately. One without the other does not work.

Assuming that you can practice fairly consistently, after one month you will have gone through the Clarke studies 3 or 4 times, the Schlossberg drills 9 or 10 times, and the Arban etudes twice or so. At this point I like to make a few changes.

Keep your Clarke routine the same. It may be hard to imagine, but many prominent trumpeters have made a point of doing the Clarke studies for years. Keep in mind the old adage “form follows function” – if, on a daily basis, you establish a very efficient, relaxed approach to playing the trumpet, you will eventually become a trumpeter that can, on a daily basis, play the trumpet in a relaxed, smooth, and expressive manner.

We’ll now change our routine a bit.

After Clarke, alternate days of Arban and Sachse 100 Etudes. On your Arban day, keep working on the 14 Characteristic Etudes, one a day. Try this: do the last third or so a couple of times, the middle third twice, and the same with the first third. Rest at least five minutes, and try to play all the way through. With Sachse, start with No. 1, and do it in every transposition you can, including ones that might not be indicated. After this month of practice, you should be through about 15 of them. I recommend setting a goal of eventually doing all 100, in every key possible, which will take about two years. (As a student, I needed more than three, because I found it very hard to keep working on these when I was sounding so bad. After I was about halfway through the etudes, I started seeing real results, and was much more motivated to continue.) Transposition needs to eventually be as automatic as possible and the trumpeter that relies on formulas will be easily rattled under pressure. Formulas are necessary to help us learn how to transpose, but if you are serious you will want to progress to the point where you do not have to rely on them. The only way to make transposition nearly automatic is through learning a large volume of material over a fairly long time, which the Sachse book is made for. Many other benefits will be evident, if you persist on these etudes in every key possible. Mix up your approach – one day, start at the lowest key and work up by half steps. Another day, do the reverse. You can also start in the middle, and progress in half steps, alternating going up and going down, so you radiate outward from the middle.

After your etude work, rest awhile. At this point we’ll alternate our Schlossberg work with a book like Charles Colin Lip Flexibilities. You should by now have a good command of the Schlossberg exercises, and can start to perform them with more intensity (wider dynamic contrasts, more variety in styles of articulation). When these exercises a played really well, they can sound like very dramatic orchestral excerpts. On alternate days, do this routine from the Charles Colin book – No. 3, No. 9, No. 21, and pages 35 & 36. If your high D is coming out with ease, move on to the next level, but stick to about five exercises. Remember that these are primarily tongue level exercises, and must be performed with a dynamic, powerful air stream in order to realize the benefits. Rest at least as long as you play.

The reason we have switched the order is to make our practice routine a bit more in line with what sport medicine research has taught us about how to improve and get stronger. Begin by connecting with your body on a relaxed easy level, then move on to skill practice, and end by working on our power and strength.

Here are a few other ideas for summer practice

1) Pick one or two of our most challenging excerpts, and really work toward mastering them. Two that most trumpeters will have to contend with many times are the Ballerina’s Dance from Petroushka and the Ravel Piano Concerto. Since they present some of the same problems, this approach will work well for both. Do 20 reps of either excerpt at a session, like this – 5 times at Quarter = 96. 5 times at Quarter = 108. 5 times at Quarter = 126 (this will not really be possible for most players, but hang in there and do your best). And then 5 times at Quarter = 108-116 (this is a common performance tempo and will feel relatively easy after what you have just gone through!). If you devote a month or two to each excerpt this way, you develop the skill and reflexive memory that will allow you to quickly reclaim these solos whenever you have to play them in the future.

Memorization is not a special virtue in itself, but being able to play music by memory, whether a transcription of a great improvisation or a favorite etude, allows us to practice in a very productive way. When we can play without constantly looking at a page of written music, we often hear ourselves better and can really connect with our playing, both consciously and subconsciously. The method described earlier of learning the Arban etudes (working from the back to the front) is a very effective way to memorize music. When you get in the habit of doing some of your practice in this way, you will find that you will temporarily memorize whatever music you are working on.

3) If you are planning a recital in the coming year, begin working on deciding the repertoire and get some real time in on playing through it, making a special point to isolate and master the hardest parts.

Finally, if you are lucky enough to find yourself around some really fine musicians, play for them – especially if they are not trumpeters. Ask them to criticize you as hard as they can. Write down what they say, so you can think about it. What they say might not make a lot of sense at first, but you may find yourself eventually learning things that will surprise you.

Chris Gekker

Efficient Embouchures

03/11/18

Efficiency is the key to great brass playing.

I believe voice may be the most difficult instrument to teach as everything important happens internally and therefore cannot be observed. The other end of the spectrum could be piano or stringed instruments: difficult to play, yet everything, or nearly everything, important to basic technique can be observed. Performing on brass instruments is closer to the singing end of the spectrum: valve and slide technique, while important and visible, are not the crux of the matter.

I believe voice may be the most difficult instrument to teach as everything important happens internally and therefore cannot be observed. The other end of the spectrum could be piano or stringed instruments: difficult to play, yet everything, or nearly everything, important to basic technique can be observed. Performing on brass instruments is closer to the singing end of the spectrum: valve and slide technique, while important and visible, are not the crux of the matter.

One may observe great embouchures in action by watching the German Brass. Their videographer tends toward closeups that offer the opportunity to observe virtuoso performing in detail. The most startling aspect is the appearance that the performers seem to be doing nothing whatsoever: their embouchures seem immobile and mostly relaxed. The piccolo trumpet playing of Mathias Höffs is especially impressive. His playing seems effortless because one does not see any embouchure motion. He uses firm, frowning corners that never move to set an efficient aperture: all of the work is in the internal tongue dance.

These two videos of transcriptions of works by Bach are especially good examples of efficient embouchures in action:

Bach BWV 972 after Vivaldi Violin Concerto RV 230

Bach Toccata and Fugue in C major BWV564 Adagio

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technology offers new ways of viewing internal activity. The video of Sarah Willis playing french horn while being observed via MRI scanning is some of the best 'internal' observation yet recorded--the importance of the tonguing for changing pitches cannot be overstated. Watching her tongue ascend until it appears tp be pressed against the roof of her mouth explains the secret of achieving the highest pitches.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technology offers new ways of viewing internal activity. The video of Sarah Willis playing french horn while being observed via MRI scanning is some of the best 'internal' observation yet recorded--the importance of the tonguing for changing pitches cannot be overstated. Watching her tongue ascend until it appears tp be pressed against the roof of her mouth explains the secret of achieving the highest pitches.

Because the technique is mostly internal, great brass playing appears easy, almost magical. Brass playing is not literally effortless, but, an efficient embouchure can make it seem so. Firm, stable corners, with a slight frown and a flat chin are the hallmarks of an efficient embouchure. Exercises that help create such stable embouchures include free buzzing, mouthpiece buzzing, pitch bends, breath attacks and pedal tones. Special Studies by John Daniels offers a good approach to many of these techniques.

One may observe great embouchures in action by watching the German Brass. Their videographer tends toward closeups that offer the opportunity to observe virtuoso performing in detail. The most startling aspect is the appearance that the performers seem to be doing nothing whatsoever: their embouchures seem immobile and mostly relaxed. The piccolo trumpet playing of Mathias Höffs is especially impressive. His playing seems effortless because one does not see any embouchure motion. He uses firm, frowning corners that never move to set an efficient aperture: all of the work is in the internal tongue dance.

These two videos of transcriptions of works by Bach are especially good examples of efficient embouchures in action:

Bach BWV 972 after Vivaldi Violin Concerto RV 230

Bach Toccata and Fugue in C major BWV564 Adagio

Because the technique is mostly internal, great brass playing appears easy, almost magical. Brass playing is not literally effortless, but, an efficient embouchure can make it seem so. Firm, stable corners, with a slight frown and a flat chin are the hallmarks of an efficient embouchure. Exercises that help create such stable embouchures include free buzzing, mouthpiece buzzing, pitch bends, breath attacks and pedal tones. Special Studies by John Daniels offers a good approach to many of these techniques.

Answers from Chris Martin

19/05/16

1. Question: Do you do your fundamentals on Bb or C trumpet ? and why

Answer: I incorporate 5 or 6 horns in my regular practice. Each day I play Bb, C, Picc, Rotary C or Bb, and Eb. I often do much of my warm-up on the Bb but am wary of becoming a slave to a certain routine. It's maybe ironic, but the most important part of my "routine" is variation. I like the "depth" of sound and blow I get with the Bb (the point of focus and balance is deeper in the Bb horn than the C). And I find if I'm too many days on just the C the sound gets a little narrow. Balance and variation around your core fundamentals practice is key.

2. Question: How did you develop your practicing skills in college to go from good to great?!

Answer: I played a lot in college. I practiced a lot every day (often too much honestly), played in brass quintets, jazz bands, recitals, all the usual things students do.

An important lesson for any trumpeter to learn is pacing: pacing in a large symphony, pacing in a concerto, pacing in a practice session and even over the course of a longer period of time. My time at Eastman taught me how to balance my desire to perform as much as possible in as many different kinds of musical settings with the necessary practice hours to take care of my fundamental playing. I'm grateful for that lesson, as I'm conscious each day of that balance. Playing 160 concerts a year with the CSO along with chamber concerts and solo appearances requires planning and organization so that I don't lose good basics of sound, articulation, flexibility, intonation.

Regardless of my schedule, I'm in the practice room every morning for a 45 minute nuts & bolts session (and usually another one at night.)

3. Question: With as much as you play your instrument, do you have unsuccessful playing days with the trumpet? And if so, how do you go about making it a successful practice session, orchestra rehearsal, performance, recital etc?

Answer: Sure I have bad days. I try to minimize the severity, so that (hopefully) I'm the only one who notices. Usually tough days for me are the result of fatigue: not so much being tired from one hard concert but an accumulation of fatigue over a period of weeks or months. Once the CSO is in full swing it's like a marathon from September to July. But that long race of a season is peppered with little sprints like a Mahler symphony or a CSO Brass concert or a concerto performance.

Here are some rules I live by during the season.

1) Be ready for the long haul by starting the season or school year already in good trumpet shape. Starting behind is a recipe for fatigue and injury.

2) Stay in good playing shape with regular practice. Especially key are the morning and evening sessions for preparation and recovery.

3) Remember to rest when needed. If in doubt take a session off or even a whole day. It's much easier to make up for a lost day than work through a cut on the lip or a muscle strain-no fun!

4) Practice every style every week: big Bruckneresque fortissimo style, articulate technique as in Ravel or Stravinsky, Baroque piccolo, solo concerti or sonatas, pp accuracy. Be ready every week for anything. (Tip: Michael Sachs' orchestral excerpt book is a great way to survey your various orchestral demands.)

4. Question: What exercises and/or practice routines do you suggest for building up triple and double tonguing (both for speed and smoothness/fluidity)?

Answer: First, speed up your single tongue. The faster, smoother and more effortless your single tongue the more so your multiple tongues. Herbert L. Clarke's One-Minute Single Tongue drill is excellent. Beginning at a tempo that's comfortable but near the edge of comfort single tongue 16th notes for one full minute breathing when necessary but minimizing breaths. I try for a smooth, easy legato at a nice mp-mf with only one breath in the minute. Hold that tempo for a week; then move the metronome up a click or two or four depending on your progress. Over 8 years Clarke worked his single tongue up to 160! For the secondary "Ka" syllable I often think "Qoo". Say those two back to back a few times. Notice how the "Qoo" is more forward, closer to the teeth and helps the air burst through the lips. Practice whatever syllables you like in normal order, then reverse, then alone, any combo. Practice long lines at an easy tempo then short bars faster than is possible. It takes time to get a fast, clear articulation but always have your ideal sound in your mind as you work.

5. Question: What is the most beneficial thing you did in your practice sessions?

Answer: Tough question but here are three that come to mind:

-Long tones with lots of extreme dynamic contrast

-Shuebruk-style attack drills always expanding in range and dynamic control

-Playing along with recordings: either music minus one types or commercial recordings. This helps train our ear to match pitch, color and phrasing-essential skills for an ensemble musician.

6. Question: We all know that 90% of the guys that go to a professional audition will play perfectly or near perfectly. In your opinion what gets you the gig? Especially going to auditions out of college without having played in a professional orchestra before.

Answer: What is perfect? You could play an audition and not split or chip; does that mean it was "perfect"? What about intonation, phrasing, risk vs reward? Did you play it safe so as not to miss? Did you take too many risks and frackfest an excerpt? My point is this: perfection isn't what it's about. These things are crucial to win an audition: sound, musical sensibility, technical control, ability to judge balance, blend and intonation. Not missing any note ever is neither a prerequisite nor a guarantee of victory.

I don't feel I've ever played a perfect audition, but I'm also my own harshest critic. If I'm tougher on my playing than anyone else in the world then I know I've done everything in my power to be ready on audition day. That knowledge builds confidence which in turn builds a sense of freedom: freedom to trust yourself, take risks, and reach for your best performance. That's how you win.

7. Question: What is your warm up routine and what do you think about great trumpet player Adolph "Bud" Herseth?

Answer: Here's the rough outline of my morning routine. As I said before, it's flexible depending on what I need, but here's an overview. The times given include assumed rests as needed.

5 minutes: breathing bag, lip buzz (Stamp), mouthpiece buzz, lead pipe buzz, long tones, vocalises

20 minutes: vocalises, scales (Schlossberg, Arban, Clarke), lip slurs, multiple tongue...Various horns, dynamics, styles, mutes sometimes.

10 minutes: accuracy drills, attacks (Shuebruk, Thibaud etc), intervals: octaves, 7ths, 9ths, 13ths, double octaves (Bai Lin, Schlossberg, etc)

10 minutes: music. Etudes, solos, symphonies, unaccompanied pieces, etc.

Again, this is a rough outline. I try and balance consistency with variety. I never want to feel I MUST do this routine to play, and I always want to finish feeling strong and ready-never tired.

8. Question: In your experience, what has been the most important element for preparing an orchestral audition?

Answer: Make a schedule for preparation with the goal that by the audition day you can play the entire list (and preferably twice through) in any order at any time of day. Making a schedule helps identify holes in your preparation and gives you a body of work to look back on, analyze and feel good about.

9. Question: What was the one thing that influenced your playing the most?

Answer: Listening and matching (or trying to match) the great players of our time.

10. Question: Chris, how you describing your sound with the CSO brass section? How do you think it should be? Some advices about sound?

Answer: I've been in love with the CSO brass sound since I was too young to play. I always try to meet the tradition of this orchestra and its historic sound as far as I can without losing my voice. Adolph Herseth made such an impact here because he was such a unique voice, but his sound wasn't born in a vacuum. He was influenced by Glantz in NY, Mager in Boston, his experiences in big bands and surely many other factors as he created his trumpet voice. You and I are no different. We are each born with a certain sound, but the more we listen and open ourselves to the possibilities of what we might do the further we can expand our own voice.

11. Question: What are some of our tips for expanding range?

Answer: Get up there every day and try! I'm not a natural high note player, so I play up there often. Keep the high range practice short in duration but high in energy and commitment. Think about "streaming" your sound horizontally through high notes. Practice up there slurred or very legato tongue before adding articulation. Strong attacks help the high range. So, if you can blow into a high D connected without the attack, then when Strauss gives you a nice forte accent in Alpine it's cake! (Well mostly.)

12. Question: Is there a better way to get familiar with the etudes when limited on time?

Answer: Slow practice rules for learning quickly. 10 minutes of slow practice equals an hour at a tempo faster than you can process; that's my experience. Slow your tempo and your brain down and you'll learn it right the very first time you read it.

13. Question: You have one of the most fluid sounds ever! What are some suggestions at attaining such fluidity and smoothness in the sound?

Answer: Read Jay Friedman's articles on trumpet playing at jayfriedman.net. The man heard a heck of a lot of good trumpet playing over the years.

14. Question: Do you think aspiring orchestra players in general need to play large diameter mouthpieces?

Answer: Orchestral players should play the largest mouthpiece made. I'd recommend starting with the Bach 1, and if that's too small find a custom shop and open it up bigger. Not really. Mouthpieces are as individual as our sounds. I play the deepest cup I can and still have brilliance and control-sometimes it's a C, sometimes it's a B. Just depends. I play a smaller rim than I did 10 years ago, and I haven't been fired yet.

15. Question: What is the most important skill you need as a section trumpet player? Why?

Answer: John Hagstrom has a terrific interview series in The Brass Herald coming out now where he discusses this. The skills are no different from any other good musician: attentive listening, pitch and tone control, flexibility.A selfless, flexible attitude is really vital. Playing section trumpet is tough. You're not playing 1st, but you're still a solo voice. Having a confident mindset and humble attitude ready to solve problems is ideal. An orchestral section must also fit in with the brass section, winds and strings, and so being able to listen beyond the confines of trumpets and brass will win you friends in an orchestra quickly.

16. Question: Hey Chris! What do you think is the best (or your favorite) transposition or arrangement for trumpet solo? with or without accompaniment?

Answer: Anything Jens has done!

S-M-P

29/12/15

In March of 2015 I attended a masterclass given by tubist, Charles Villarrubia, at the Northwest Brass Festival. I had met Charlie, briefly, years before when we were both in Boston and knew him to be a spectacular tubist, even so, I was stunned by his insight and artistry.

At the masterclass I asked Charlie for a few ‘light-bulb' moments; that is, words, instructions, or excercises that his teachers had employed that had an immediate impact upon him as a player. The techniques he described came from not just tubists, but from a myriad of sources including violinists, singers and other wind musicians. This receptive approach is one of his strengths; his curiosity leads him to seek out new ideas and he accepts productive methods from wherever they come. His response provided some practical tips, and also exposed some of the roots of his success.

He mentioned in passing one of the secrets to his success: his practice routine. He is in his studio at 8:30am warming up everyday. He doesn’t practice when he feels like it, he practices on a set schedule which is nearly unchanging. To instill this ideal into his students he requires them to fill out a practice schedule every week. Not a report on how many hours they practiced last week, but rather exactly when they will practice in the coming week, i.e., scheduling practice as firmly as any class they might be taking.

His first tip relates to the importance of practicing fundamentals. His early practice session begins with work on exercises from The Brass Gym such as tonguing, slurring, scales, range and endurance--every day. As he drives to his studio at the University of Texas, Austin, he performs breathing exercises, so that when he walks into his studio he is mentally and physically prepared.

The practice technique that he learned from Marianne Gedigian, a flutist and his wife, is the 'Fermata Method.' One plays the first two notes of a phrase adding a fermata to the second note. If the note with the fermata sounds great, then one begins again, this time placing the fermata on the third note. If the fermata note is not great, one repeats until the tone is perfect--the tone, not the note. The musician continues this process until the phrase is complete. This technique is especially helpful for conquering large intervals, i.e. not letting the distance from the previous note impact the quality of the note on which the fermata rests.

For technical passages he likes to practice at 70% speed. If one practices more slowly the fundamental connection of air to note can become distorted. Charlie finds that around 70% of tempo allows him to maintain his usual technique but also overcome difficulties with fingers.

S-M-P comes from his days as a student, when his teacher, Neal Tidwell, tubist for the New Orleans Symphony, would frequently write this on the top of an assignment. S-M-P stands for Sing-Mouthpiece-Play. When Charlie was assigned an etude, he was required to sing, then buzz on his mouthpiece, then, finally, play each phrase on the tuba. This gets to the core of Charlie’s strength as a musician. He doesn’t simply play tuba, he sings music. His core intent is to deliver a musical idea, and he happens to use tuba as his basic tool: his musical impulse is rooted in the lyricism of singing. What is most impressive about a performance by Charles Villarrubia is that, even in the most technical music, such as the Carnival of Venice by Arban, one is most impressed not by his formidable technique, but by his beautiful, lyric tone.

Fast practice

29/12/13

Jason Sulliman has posted a great video on fast practice. Rather than starting slowly and clicking up the metronome, fast practice involves starting at tempo but with only a small portion of the passage, gradually adding notes. My favorite method is to start at the end of a passage and to keep adding beats to the front of the lick.

Check out his video on Youtube:

Check out his video on Youtube: